The Evolution of Stabilizers

A look at how today’s embroidery stabilizers evolved from interlining used by the sewing industry.

By Fred Lebow

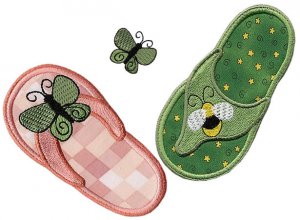

Embroiderers today have it so good. Fast yet affordable machines, high-tech framing devices, and other advances have made a decorator’s job easier than ever before. But there’s another critical area that has seen equally impressive developments throughout the years, even though it doesn’t get as much attention and that’s stabilizers.

With very few exceptions, stabilizers provide the foundation for all commercial embroidery. They have come a long way from the earliest versions, which were borrowed from the apparel manufacturing industry. In those days, the most commonly used versions were stiff interlinings made out of materials like horse hair and canvas for lining pockets, collars, and coats. In addition to being stiff, they often were scratchy and rough against the skin. There is no comparison to the soft stabilizers available today.

The introduction of specialized, commercial stabilizers in the late 1970s was of great significance to the burgeoning embroidery industry and played a role in today’s widespread acceptance of embroidered goods by the public. This new generation of stabilizers improved registration significantly. They draped better and were much softer against the skin. Instead of a stiff board behind an embroidery, you had something that was not visible to the eye from the front of the garment. Another plus was that embroiderers had a material that was the perfect weight and thickness. They no longer had to use multiple layers, which often added unsightly bulk to a design. These new materials saved time because they were quicker to use and money because you needed less of them.

How Stabilizers Got Started

I started in the embroidery industry in 1975, working for John Solomon, a distributor, selling interlinings made from polyester rayon to apparel designers. As I traveled the country and visited manufacturers who had in-house embroidery —typically large houses with 30 to 50 automated machines using Schiffli and Gross equipment — I noticed a need for a more specialized stabilizer.

In those days, embroiderers’ options for stabilizers were few, and they tended to use sewing interlinings or whatever else they could get their hands on such as cardboard and paper, often in multiple layers to provide enough stability.

The Manufacturing Process

The biggest breakthrough in embroidery-specific stabilizers came about when a new manufacturing process was developed called wet-laid. Sewing interlinings are made with a dry-laid process and includes two types: carded saturate or random. This produces a one-directional material, meaning it stretches in one direction. This works fine for interfacings—but is not ideal for embroidery.

The wet-laid process is similar to how a high-quality paper is made. Fiber is dispersed in a solution. A screen rises and the solution dries yielding a multidirectional and uniform nonwoven material.

This new wet-laid process was ideal because the goal of an embroidery stabilizer is to help achieve proper fabric tension in the hoop. It should be taut, like a tambourine skin, with the tension spread evenly in all directions. This is called multidirectional or nondirectional tension. If the stabilizer is too loose, the needle deflects and design registration is adversely affected. Wet-laid stabilizers do not stretch in any direction and provide a smooth, uniform surface.

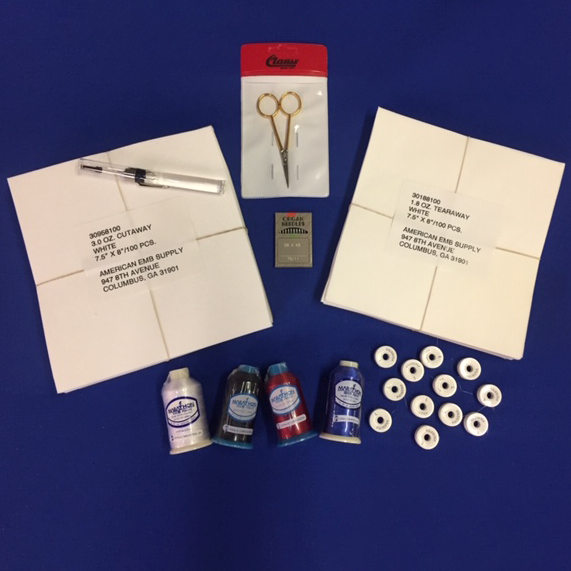

Initially, this thin, wet-laid, nonwoven material was used for pocket welts, but it was soon discovered to also work well as an embroidery stabilizer. The first version, which was made by International Paper, was a 1.5-ounce cutaway that included silicone, which aids in needle glide. This density was suitable for medium to low stitch counts and was soon followed by a variety of additional weights for other applications.

Steady Progress

Other innovations followed. High-volume embroiderers needed a stabilizer that could be quickly torn away instead of cut away with scissors, which could be a time-consuming process. To meet this need, a nonwoven tearaway stabilizer was created with a higher percentage of rayon to polyester than cutaway. The rayon allows for tearability, while the polyester maintains the durability.

Soon after came tearaway with longer fibers, which provided better stability and felt softer against the skin, although it admittedly didn’t tear quite as well. Eventually, a manufacturing process called “confil,” was invented by a French company. This involved preheating the fibers, which allowed for shorter polyester fibers that still bonded. This material was easier to tear.

On white or light-colored garments, such as piqué knit golf shirts, you often could see the square of stabilizer through the front of the shirt. To eliminate this problem, no-show nylon mesh stabilizer was developed. Offered in white, black, and beige, this made the classic left-chest embroidery on a polo shirt invisible from the front and provided a super soft layer against the wearer’s skin.

Another challenge to solve was how to embroider on items that did not fit in a hoop such as baby socks, ties, and collars. The first solution came in the form of adhesive sprays but these released toxin fumes into the air and often gummed up the needle and other machine parts. In 2000, I helped develop a product called Hydro Stick. This product was hooped and then the top was lightly moistened with water and the embroiderable would stick to it. It could then be embroidered with a backing even though it did not fit in the hoop.

Fusible stabilizers also were developed and primarily used in the home single-needle machine industry for users who wanted the stabilizer to hold securely in place when sewing. However, the first generation of fusibles often required such a high heat to melt the adhesive; it would scorch or damage fabrics, especially delicate ones. The solution to this was a low-melt fusible backing, which provided a better bond at a lower temperature.

Many times, embroiderers wanted to decorate items where both sides would show. This meant a stabilizer was needed that could be completely removed upon completion of sewing. Water-solubles were developed for this purpose. Used for heirloom work, towels, and free-standing lace, this type of stabilizer completely dissolves in water leaving no trace.

On the Horizon

These are just a few of the many developments that have taken place in embroidery stabilizers over the years. It would be difficult to mention them all. But the age of innovation and the development of new products are not over. Look for suppliers to continue making progress in stabilizer technology, including different types of fusibles and other specialty products that will help embroiderers decorate an even wider range of products more easily and with better results.

SIDEBAR

The Process Of Creating A New Stabilizer

Creating, testing, and introducing new stabilizers is no simple matter. And what many embroiderers may not realize is none of the leading suppliers of stabilizers actually manufacture their product. All stabilizers are made by fabric mills that work with a developer or product designer to come up with the right recipe to get the job done.

The way this process works is a developer comes up with the idea. He goes to a mill and discusses with the mill’s engineers and chemists if his idea can be done. Next he submits a proposal, which must include a financial commitment; otherwise the mill is not interested. For instance, when I developed Hydro Stick, I had to commit to the mill for a million yards, even though I initially needed only about 3,000 yards for testing.

If the proposal is accepted, the developer works with the mill’s engineers, tweaking the technology and getting a few large embroidery houses to test the new material 1,000 yards at a time. After getting their feedback, the technology is fine tuned, and the process is repeated until the stabilizer is perfected. Reaching that point is a long process. Typically, it will take between two and three years from concept to finished product.

BIO

Fred Lebow has been developing nonwovens and interlinings for the sewn products market for 31 years. For the past 20 years, he has focused on embroidery stabilizers and has been a pioneer in the development of many new products that are in widespread use today.

By Fred Lebow

Embroiderers today have it so good. Fast yet affordable machines, high-tech framing devices, and other advances have made a decorator’s job easier than ever before. But there’s another critical area that has seen equally impressive developments throughout the years, even though it doesn’t get as much attention and that’s stabilizers.

With very few exceptions, stabilizers provide the foundation for all commercial embroidery. They have come a long way from the earliest versions, which were borrowed from the apparel manufacturing industry. In those days, the most commonly used versions were stiff interlinings made out of materials like horse hair and canvas for lining pockets, collars, and coats. In addition to being stiff, they often were scratchy and rough against the skin. There is no comparison to the soft stabilizers available today.

The introduction of specialized, commercial stabilizers in the late 1970s was of great significance to the burgeoning embroidery industry and played a role in today’s widespread acceptance of embroidered goods by the public. This new generation of stabilizers improved registration significantly. They draped better and were much softer against the skin. Instead of a stiff board behind an embroidery, you had something that was not visible to the eye from the front of the garment. Another plus was that embroiderers had a material that was the perfect weight and thickness. They no longer had to use multiple layers, which often added unsightly bulk to a design. These new materials saved time because they were quicker to use and money because you needed less of them.

How Stabilizers Got Started

I started in the embroidery industry in 1975, working for John Solomon, a distributor, selling interlinings made from polyester rayon to apparel designers. As I traveled the country and visited manufacturers who had in-house embroidery —typically large houses with 30 to 50 automated machines using Schiffli and Gross equipment — I noticed a need for a more specialized stabilizer.

In those days, embroiderers’ options for stabilizers were few, and they tended to use sewing interlinings or whatever else they could get their hands on such as cardboard and paper, often in multiple layers to provide enough stability.

The Manufacturing Process

The biggest breakthrough in embroidery-specific stabilizers came about when a new manufacturing process was developed called wet-laid. Sewing interlinings are made with a dry-laid process and includes two types: carded saturate or random. This produces a one-directional material, meaning it stretches in one direction. This works fine for interfacings—but is not ideal for embroidery.

The wet-laid process is similar to how a high-quality paper is made. Fiber is dispersed in a solution. A screen rises and the solution dries yielding a multidirectional and uniform nonwoven material.

This new wet-laid process was ideal because the goal of an embroidery stabilizer is to help achieve proper fabric tension in the hoop. It should be taut, like a tambourine skin, with the tension spread evenly in all directions. This is called multidirectional or nondirectional tension. If the stabilizer is too loose, the needle deflects and design registration is adversely affected. Wet-laid stabilizers do not stretch in any direction and provide a smooth, uniform surface.

Initially, this thin, wet-laid, nonwoven material was used for pocket welts, but it was soon discovered to also work well as an embroidery stabilizer. The first version, which was made by International Paper, was a 1.5-ounce cutaway that included silicone, which aids in needle glide. This density was suitable for medium to low stitch counts and was soon followed by a variety of additional weights for other applications.

Steady Progress

Other innovations followed. High-volume embroiderers needed a stabilizer that could be quickly torn away instead of cut away with scissors, which could be a time-consuming process. To meet this need, a nonwoven tearaway stabilizer was created with a higher percentage of rayon to polyester than cutaway. The rayon allows for tearability, while the polyester maintains the durability.

Soon after came tearaway with longer fibers, which provided better stability and felt softer against the skin, although it admittedly didn’t tear quite as well. Eventually, a manufacturing process called “confil,” was invented by a French company. This involved preheating the fibers, which allowed for shorter polyester fibers that still bonded. This material was easier to tear.

On white or light-colored garments, such as piqué knit golf shirts, you often could see the square of stabilizer through the front of the shirt. To eliminate this problem, no-show nylon mesh stabilizer was developed. Offered in white, black, and beige, this made the classic left-chest embroidery on a polo shirt invisible from the front and provided a super soft layer against the wearer’s skin.

Another challenge to solve was how to embroider on items that did not fit in a hoop such as baby socks, ties, and collars. The first solution came in the form of adhesive sprays but these released toxin fumes into the air and often gummed up the needle and other machine parts. In 2000, I helped develop a product called Hydro Stick. This product was hooped and then the top was lightly moistened with water and the embroiderable would stick to it. It could then be embroidered with a backing even though it did not fit in the hoop.

Fusible stabilizers also were developed and primarily used in the home single-needle machine industry for users who wanted the stabilizer to hold securely in place when sewing. However, the first generation of fusibles often required such a high heat to melt the adhesive; it would scorch or damage fabrics, especially delicate ones. The solution to this was a low-melt fusible backing, which provided a better bond at a lower temperature.

Many times, embroiderers wanted to decorate items where both sides would show. This meant a stabilizer was needed that could be completely removed upon completion of sewing. Water-solubles were developed for this purpose. Used for heirloom work, towels, and free-standing lace, this type of stabilizer completely dissolves in water leaving no trace.

On the Horizon

These are just a few of the many developments that have taken place in embroidery stabilizers over the years. It would be difficult to mention them all. But the age of innovation and the development of new products are not over. Look for suppliers to continue making progress in stabilizer technology, including different types of fusibles and other specialty products that will help embroiderers decorate an even wider range of products more easily and with better results.

SIDEBAR

The Process Of Creating A New Stabilizer

Creating, testing, and introducing new stabilizers is no simple matter. And what many embroiderers may not realize is none of the leading suppliers of stabilizers actually manufacture their product. All stabilizers are made by fabric mills that work with a developer or product designer to come up with the right recipe to get the job done.

The way this process works is a developer comes up with the idea. He goes to a mill and discusses with the mill’s engineers and chemists if his idea can be done. Next he submits a proposal, which must include a financial commitment; otherwise the mill is not interested. For instance, when I developed Hydro Stick, I had to commit to the mill for a million yards, even though I initially needed only about 3,000 yards for testing.

If the proposal is accepted, the developer works with the mill’s engineers, tweaking the technology and getting a few large embroidery houses to test the new material 1,000 yards at a time. After getting their feedback, the technology is fine tuned, and the process is repeated until the stabilizer is perfected. Reaching that point is a long process. Typically, it will take between two and three years from concept to finished product.

BIO

Fred Lebow has been developing nonwovens and interlinings for the sewn products market for 31 years. For the past 20 years, he has focused on embroidery stabilizers and has been a pioneer in the development of many new products that are in widespread use today.